The future we share. On platform cooperativism, data commons & Web3 - in coversation with Jan J. Zygmuntowski

Hi! At Golem Foundation we’re all about discovering different ideas for creating a better digital future in which the user is put first. To explore some of them, we recently sat down with Jan J. Zygmuntowski - a Polish economist, PhD candidate at Koźmiński University, Director at the CoopTech Hub and President of the Instrat Foundation. We talked about cognitive capitalism, why and how we can try changing the current set up through ideas such as platform cooperativism and data commons, and how joining forces with Web3 might bring about great things, not just utopian visions.

In your book Kapitalizm sieci (Network Capitalism) you explain that we’re living in the times of cognitive capitalism. What is this incarnation of the ‘regime of accumulation’ about? What are we accumulating?

To describe what today’s economic system looks like requires a redefinition of what is at the core of capitalism. Most economists believe that we define capitalism as a system of the accumulation of capital. As we transitioned to industrial capitalism, capitalists shut off large pieces of land - various common spaces were seized and turned into private property, which is a commodity. Since capital allows the acquisition of labor and the conversion of labor into a commodity, it is possible to multiply it continuously. This is the basic force behind capitalism - only an accumulated commodity is secure, as it becomes somewhat autonomous, an agent of the system. Capitalism is also a regime of accumulation because it is not just the action of money alone, but an arrangement of all possible institutions.

When patents appeared during the industrial revolution, knowledge bore some importance, but it was still incidental. At the core of industrial capitalism was coal, steel and physical labor. After World War II, jobs like sales professionals and managers gradually started to become more important. The biggest change came with the advent of digital technologies, as it became possible to drill deeper and deeper into the structure of information. It’s hard to trade patents, but it’s very easy to trade information, or even individual items of data. And it’s becoming increasingly easier to extend this regime to things that we didn’t regard as work before, like scrolling through Facebook, which provides value to the tech giants. 20 years ago the top companies in the world ranked by market capitalization were all industrial companies; but we’re in a situation today where all of the top companies ranked by market cap are technology companies, which are taking advantage of the high value of data and information. So capitalism has reoriented itself; yes, industrial capitalism continues to exist and is part of our system, but what is really valuable today is information. Capitalism is nowadays also cognitive in the sense that in this incarnation it is about the workings of the human mind.

There seems to be a lot of talk about the dangers of using “free” services, yet people still use them, often aware of the real cost of doing so.

I’m not sure if it’s a matter of these services being free: there are studies on how much people would be willing to pay for services, such as an ad-free Facebook. And we do pay for some things. Take podcasts and texts - more people are paying for these every year, and the whole creator economy is booming. We are willing to support artists or creators if we see that what they do is valuable to us. So I don’t know if it’s not simply a question of feeling like we have no alternative - through the network effect, the technological infrastructure itself favors monopoly. Historically it’s been pretty clear what to do with monopolies.

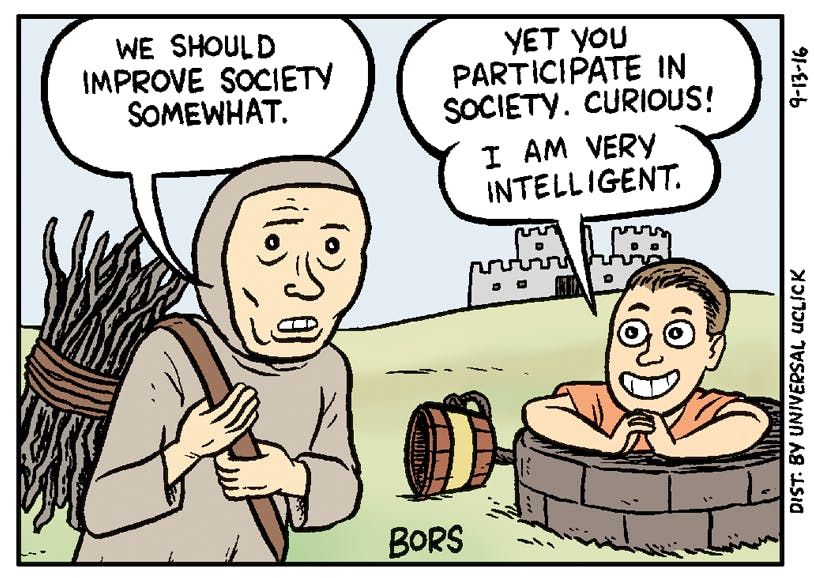

From Adam Smith to all the radicals, everyone said they had to be under public control: either nationalized or very heavily regulated. In the case of these big tech platforms, we have allowed them to grow as private natural monopolies, and they have reached such a scale that we feel we have to use them, even if it leaves a bad taste in the mouth, otherwise we would end up outside society. There is a sense of having no alternative. There’s often this criticism that since we’re all using the same thing, there probably isn’t a problem. If there was, we’d all walk away from this Facebook thing and everything would stop. It’s cool to boycott, but I’m reminded of a meme where a peasant says, “We should improve society”. And immediately out of a well pops a guy who replies, “Ha, that’s interesting! Because you still participate in society!” It’s not that we should all hide away in a cave and wait for all the new alternatives to emerge in the world.

Matt Bors “Mister Gotcha” The Nib

And what can we gain by searching for these alternatives?

Let me start by saying that the cooperative lesson from a century ago should be the basis for action today for those who are in Web3. This lesson is a perfect parallel - at that time it was also about decentralization, and the movement was not created by outliers, or people completely outside of society, but often by those who were small entrepreneurs, merchants, and farmers, who already knew that a strictly individualistic attitude would lead to them being crushed by corporations. They too were faced with this dilemma: how to convince people to do the hard work of democratically managing their first cooperative. Even today, we face similar problems while teaching people about digital cooperatives: after all, it takes a lot of energy to establish something democratically, to convince each other. Majority voting is not the best way to make decisions at all, because it just creates a certain group that feels they were not heard and lost the vote. It may be 49.9 percent of the people, but they’re going to be thrown overboard.

I have a feeling that the lesson of building social capital laboriously, organically, convincing more people, collecting those small resources that those small entrepreneurs had back then, is a lesson for those in the decentralization space today. The only thing I would caution against: I get the idea that some people around Web3 are of the opinion that technical protocols alone are a solution in themselves. This is just another form of the technosolutionism offered to us by the tech giants who say, “There is only one direction of technological progress and because the metaverse will be modern, it will be good”. In Web3 there seems to be a similar sentiment that decentralization in itself is good. Take distributed ledger protocols: some say if we use distributed ledger technology we will have a more equal and just society. Yes, you can include these values in the technological structure itself - governance by algorithms is a fact - but you have to know from the outset what values you want to include there.

Decentralization is a tool, but for what? We have to answer this question for ourselves. Do we mean to democratically manage the platform? If so, then protocols based on Proof of work are completely unsuitable for this, because they favor those who are ready to buy more equipment to participate in the network. Decentralization is a step in the right direction, but that’s not the only point. Breaking up monopolies and pluralism is a good idea, but if we broke up Facebook into a hundred platforms all competing equally for our attention and data, I suspect we’d be faced by an even bigger surveillance nightmare.

So let’s look at the idea of platform cooperativism. Could you explain it by talking through what you do at CoopTech Hub?

Our job at CoopTech Hub is to bring the concept of platform cooperativism to the people and implement it in Poland. There is a passion and belief in the platform cooperativism space that it makes sense. A few years ago I came across the Fairbnb project, which is like Airbnb, except that half of the revenue remains in the cities for the development of social projects, community housing, and it bans big investors. At that time, there were just a few cities listed, mainly in southern Europe, today it’s over 30 cities. Soon we as CoopTech Hub will introduce Fairbnb to Poland, which goes to show it is developing, slowly but gradually. With more regulations, people start to look for alternatives and it turns out that some are already there: whether it’s Fairbnb, which wants to change tourism, or Up & Go, which is a cooperative of cleaning workers. This is not a case of uberization; on the contrary, these solutions empower workers.

There are also examples based in Web3: in Europe we have an electric car sharing cooperative (Mobility Factory), which is now developing a protocol to share value and oversee the whole network, which will be pan-European. In Poland we are also trying to educate people, including local government, on how to make the connection between cooperatives and technology. Cooperatives offer Poland’s ‘medium-sized’ cities the chance to rebuild their local economies, following the proven model of community wealth-building. They currently spend a huge amount of money on buying in software from outside, yet people are running away to larger metropolises. We say reverse that logic. Build local digital cooperatives that generate revenue and employ people, and gradually you will see your cities rebuild.

What about alternatives we can look for on the macroeconomic level? The so-called data commons model seems particularly interesting.

Data is produced by employees of Uber, for example, and cities have a lot of data that is produced in their territories. In Poland we have data from health care, which is often scattered: some of it is in the National Health Fund, some in private medical clinics, some of it we can have, say on our Apple Watch, and some of it is what we create while using social media. The potential of the latter is exploited all too much, but for socially disadvantageous purposes. Data is a resource that has value only through aggregation, and my personal data is worth very little on its own. However, when we realize what a valuable resource data is when it belongs to, let’s say, all of us Poles - 40 million people - or Europeans - more than half a billion people - it turns out that it is a resource that would let us benefit from digitization.

What’s more, it is a resource that could indicate the direction of technological development. The proposal is to go beyond the model in which data belongs to corporations and is a commodity in their hands, and to simultaneously stay away from the model in which each of us decides about our own data and sells it. Because that will just be cookie banners all over again - we’ll click “ok” to everything and earn a few cents, even though that data is worth a lot more. So the proposal of data commons which we described recently with Paul Nemitz and Professor Zoboli follows the thoughts of people like Professor Mazzucato, who has called for the creation of public data repositories.

A data commons is a trusted space for sharing data for the public good - it’s supposed to be a kind of shared data bank that I can come to as a citizen. I don’t have to ask some kind of data authority through filing a complaint. I just have, for example, an interface in an app that allows me to control all the data. But I don’t do it on some server of my own, selling the data; instead I have a data bank that keeps it safe and manages it. This infrastructure, which would be shared, would allow us to negotiate who gets access to the data, what is created with it, who owns the license to what is made, and what these creations are used for.

So data commons could reverse the direction of surveillance: going from our data being used to watch us, to us watching them and deciding what our data is being used for.

Data behaves like a common pool resource in Professor Ostrom’s understanding, which is the same as, for example, forest resources or a fishery. If we look at data in this way, we can see that abusing it weakens people’s trust in it, and they would be willing to produce less and less of it. The common pool of data that we could use as a society is under threat as we don’t want to add to it. When Professor Ostrom was thinking about the management of common pool resources, it wasn’t state-based at all. It was more of a common, or cooperative kind of thing, growing bottom up while recognized by the state. When the state accepts that there is a grassroots structure at the fishery that manages it and that there should be a dialogue with it, the government gives it various powers or concessions, but it doesn’t necessarily get involved directly. You have to think similarly about data commons: that’s why we don’t call it a state data bank. I think the role of the state is inevitable, because it has to accept the existence of data commons, interact with it, or even appoint it. But in the end, the data commons is supposed to be an entity that works by collaborative governance and brings together different actors.

What would you say to those who might think this is just a utopian way of seeing things?

Well, isn’t Web3 an even more utopian vision? Or that of the metaverse? I think we all feel that we are in some kind of trap and trying to look at the future by offering slightly different visions. I have a feeling that today Facebook is more challenged by the ideas of people who want to strengthen the public sphere, who want to socialize the Internet, and if Web3 is going to be part of a bigger plan for that, then welcome on board! Probably the people doing Web3 regard their solutions as less utopian, because they see that technologically their ideas are doable, they think that if you can write a protocol, or build a DAO, then surely that means they work. To this I say, okay, but let’s bring the economic perspective to the table: creating a data commons as an institutional mechanism is also possible - and it’s not utopian, either. Now I probably can’t do it without their technical assistance but they probably won’t be able to scale up without looking at it in terms of economics and society - so probably if we join forces something much better will come out of it.

What gets you most excited about the future you’re building?

Probably any innovator will tell you this, but I’m most excited about the moment when things that you’ve seen as a creator go from the early adopters to the population as a whole. It’s going to be a fantastic moment, in my opinion, when these individual initiatives start to scale up and thereby transform society and the economy. I’d say that for the data commons community, that moment will be when we start to build a sort of fediverse. It’s interesting that the word fediverse is older and functions as a concept already, as opposed to the metaverse, which for now is just a fancy of Zuckerberg’s imperial ambitions. I think when logging in to various cooperative platform services at the push of a button using your cooperative ID becomes a reality, or when it becomes normal to vote once a year on where our health data funds go, that will be a really fascinating moment. Then people like me will finally be widely criticized, because those who take for granted what we’ve built will say, “Hey, why didn’t you do it more like this, or like that, why aren’t there options here? We need to improve it!” And then I’ll be happy because kids will be burning my books and I’ll be able to sit back and say, “Okay, my work here is done”. You have to pass on the baton to the next generation, who has to have its own revolution. I often say this to my students: “You are the next generation of technology entrepreneurs, and I hope that when you go out there, you will start by fixing the mistakes of the previous one.”