Science fiction: the futures it inspires us to create and the ones it inspires us to leave behind

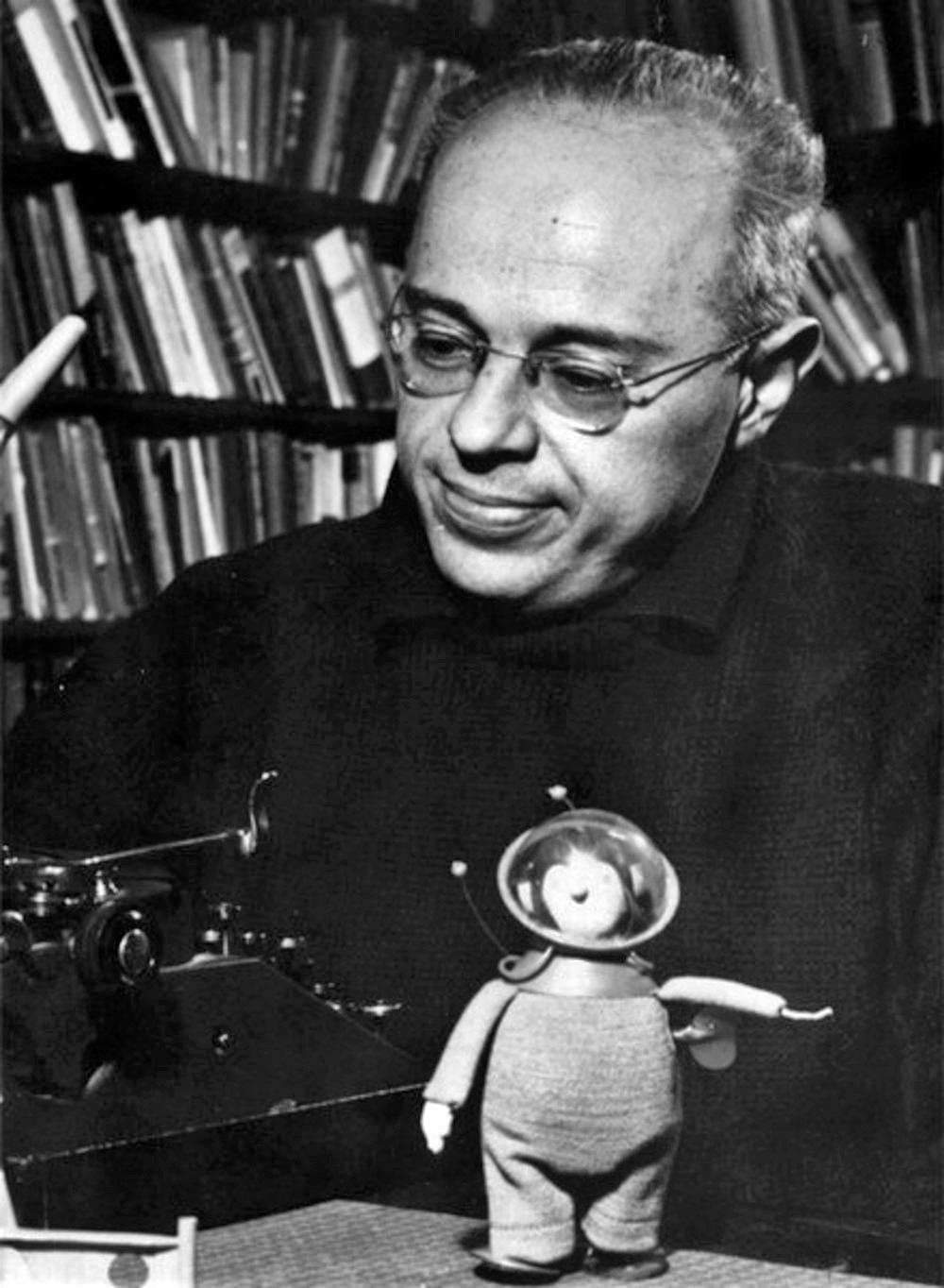

Today, Stanisław Lem, who is regarded as one of the best science fiction writers of all time, would have turned 100. He sadly passed away 15 years ago, leaving behind a considerable collection of books and essays. While his works are interesting, they also, along with other science fiction pieces, provide inspiration - both for how we could improve the world around us and for the futures we should avoid creating.

Science fiction is a genre whose history spans centuries: A True Story by the 2nd century Greek writer Lucian of Samosata is regarded by some as the first science fiction novel, or at the least one of the precursors of the genre. It includes the now familiar themes of colonizing space, traveling to distant galaxies, and alien lifeforms. It shows that our longing to explore what the world could be, both positive and negative, has always been something that has interested our ever-inquisitive species.

Rarely do we come up with ideas in a vacuum. What is perhaps one of the best things about us as a species is that we are able to collaborate - and that doesn’t necessarily mean working directly together. Sometimes it’s a case of one person’s work inspiring another, one scientific discovery leading to others, or a piece of literature providing the spark for a new invention. We associate the very act of being inspired with having the feeling that we can achieve something. It’s about making something happen having seen that it may be possible.

Philip K. Dick once said: “I want to write about people I love, and put them into a fictional world spun out of my own mind, not the world we actually have, because the world we actually have does not meet my standards.” So some may use science fiction as a way of creating a new, better version of the world - utopias even, such as the beautiful, egalitarian planet Earth in Star Trek - boldly looking beyond our current capabilities. Imagining other ways of doing things is often the first step towards making that idea happen. Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Seas, for example, was purportedly the inspiration for American inventor Simon Lake’s open-water submarine; similarly, the young Igor Sikorsky, fascinated by the ideas in Verne’s novel The Clipper of the Clouds (a.k.a Robur the Conqueror), went on to invent the helicopter.

Finn Brunton, author of Digital Cash: The Unknown History of the Anarchists, Utopians, and Technologists Who Created Cryptocurrency, explains that what all the creators of the concept of digital cash had in common was a shared sense of “science-fictional sensibility” - a specific attitude which came from from reading the American science fiction of the 1950s, 60s and 70s. And nowadays, in the age of Internet decentralization, sci-fi related themes abound. Vernor Vinge’s True Names had a major influence on the cypherpunk movement. Cory Doctorow’s books inspired legions of hacktivists and tinkerers working to undermine the Big Tech dominance over the Internet. In the Ethereum community you will often come across Daniel Suarez’ two part novel Daemon, where a computer program runs without human control.

At the Golem Foundation, you can often sense the creative mark that science fiction has left: the name Golem itself is a nod to Golem XIV, an essay by Lem which takes the form of a lecture given by a supercomputer. Careful readers of the Wildland paper should also spot a number of references to another great Lem’s work Solaris. Julian, Golem Foundation’s CEO, regards Lem’s The Invincible and Peace on Earth - brimming with the themes of hives and miniaturization - as works which can help further decentralists’ visions.

Alas, not every science fiction vision comes to fruition. Noah Smith writes that the reason we have yet to see the futures of Star Trek, The Jetsons or Asimov come to life is that we have reached the limit of both theoretical physics and energy. So perhaps some things are simply too difficult to replicate, despite the massive technological leaps we have made and our increasing understanding of physics. Perhaps some are simply unattainable according to the known rules which govern our universe. And maybe we should be grateful that some of the science fiction futures have not materialized.

Of course, while some may use science fiction as a way to imagine a new, better version of the world, a utopia even, others (or indeed sometimes the same) create worlds far from perfect, even verging on dystopian. These are often equally as exciting and interesting to read, sometimes appearing to foreshadow where the path we’re taking will bring us (many cite Orwell’s 1984 as a vision of where socialism was meant to take us). They offer a set of completely novel challenges: robots going rogue, a completely new system of oppression being put in place, or humans becoming enslaved to technology.

And in this sense, science fiction can also be an inspiration for what not to do. In his essay The Self-Preventing Prophecy, the American scientist and sci-fi author David Brin explains that being pessimistic about the future and offering dystopian visions can help prevent those very visions from becoming a reality. He writes: “I’m much more interested in exploring possibilities than likelihoods, because a great many more things might happen than actually do”. And as Brin puts it, it’s as much about avoiding mistakes as it is about planning for success. So science fiction is perhaps equally about showing us futures which we should avoid as it is about inspiring us to attain the futures it presents.

Some, like Neal Stephenson, whose works like Snow Crash, Cryptonomicon, and The Diamond Age inspired thousands of people - us at the Golem Foundation included - to work on a more private, decentralized, and user-friendly Internet, think that nowadays science fiction writers are actually being too pessimistic. He says that “sci-fi’s greatest contribution is showing how new technologies function in a web of social and economic systems—what authors call “worldbuilding.” Michael Solana, author and vice president at the venture capital firm Founders Fund, shares this sentiment, and adds to it: dystopian visions make people fear technology, while technology is the biggest game-changer in terms of bettering our society. He writes: “We must stand up and defeat our fears. (…) It is in our power to create a brilliant world, but we must tell ourselves a story where our tools empower us to do it.” On the other hand, having so many pessimistic visions may be a good remedy for all the possibilities technology has created. The more technology makes possible in general, the more dangerous potential futures it creates.

So on this day, while remembering Lem and his work, let us celebrate all the minds behind science fiction and all the futures that they have imagined: those which we would love to make happen, but perhaps never will, those which have already made our world a better place, those which will do so if the right people are inspired, and the futures which we would be better off leaving behind in the realm of fiction.